-x-x-x-

-x-x-x-

Assista algumas das entrevistas que fiz com Emerson Martins quando formamos o Jardim Alheio:

os autores são convidados a participar do quarto encontro do Ciclo de Crítica dedicado à sua obra. Foram 24 Ciclos entre 2013 e 2015, na Livraria Martins Fontes e na Casa das Rosas. Pretendo recomeçar em breve - fique atento!

-x-x-x-

Meus textos no Jornal Rascunho:

Bernardo Ajzenberg, Etgar Keret, Evandro Affonso Ferreira, Stefan Zweig, Patrick Modiano, João Carrascoza, Fania Benchimol, Tailor Diniz, e outros

http://rascunho.gazetadopovo.com.br/autor/vivian-schlesinger/

-x-x-x-

-x-x-x-

Poeta falando (bem) de poeta: Cyro de Mattos teve a generosidade de me permmitir publicar sua crítica sobre

MEMORIAL DA CASA DA TORRE

Stella Leonardos

LEIA E DESCUBRA QUEM É STELLA LEONARDOS

E O QUE É A CASA DA TORRE

|

| Inscreva-se! |

-x-x-x-

Assista algumas das entrevistas que fiz com Emerson Martins quando formamos o Jardim Alheio:

os autores são convidados a participar do quarto encontro do Ciclo de Crítica dedicado à sua obra. Foram 24 Ciclos entre 2013 e 2015, na Livraria Martins Fontes e na Casa das Rosas. Pretendo recomeçar em breve - fique atento!

link do canal do Jardim Alheio no Youtube

Link das playlists

Luiz Ruffato

Bernardo Carvalho

Joca Reiners Terron

Ilan Brenman

Jardim Alheio

Lourenço Mutarelli

Cristovão Tezza

Paulo Henriques Britto

Noemi Jaffe

Evando Affonso Ferreira

Carlos Felipe Moisés

Ricardo Lísias

Frederico Barbosa

Luiz Krausz

Clube de leitura VHS – Luiz Ruffato

Clube de leitura VHS – Michel Laub

-x-x-x-

Meus textos no Jornal Rascunho:

Bernardo Ajzenberg, Etgar Keret, Evandro Affonso Ferreira, Stefan Zweig, Patrick Modiano, João Carrascoza, Fania Benchimol, Tailor Diniz, e outros

http://rascunho.gazetadopovo.com.br/autor/vivian-schlesinger/

-x-x-x-

CLARICE LISPECTOR AND GINA BERRIAULT:

a geography of loneliness

Parallel lines in literature, by Vivian Schlesinger

Gina Berriault (1926-1999) Clarice Lispector (1925-1977)

“My strength

is in my solitude. I fear neither stormy

rain nor wild winds, for I am, too, the dark of night.” (CL)

Two women, one pose. One shoulder lowered to suggest finely angled

bones. Long thin arms that end in

bracelet-clad wrists, fingers of one hand entwined with the other, almost

naturally send the viewer back to the face.

Cheek bones chiseled by Slavic genes, eyes, no more than slits, daring

one to ask: ask, and you will not find

any answers. The eyes reveal nothing but

the fact that there is a lot to be revealed.

Born three weeks

apart, they could have been best friends, neighbors or classmates, yet they never met in person. It’s not unthinkable that they never even read

each other’s books. But Clarice Lispector

and Gina Berriault would have had a great deal of empathy for each other’s

characters, the pain of solitude their fraternal, albeit literary, bond. Lispector was born in December of 1925, Berriault

in January of 1926, one to Jewish Ukrainian parents, the other to Jewish

Lithuanian parents. The Lispector’s

emigrated to Brazil shortly after her birth, whereas the Berriault’s were

already living in the U.S when Gina was born. Both girls spent all their childhood years in

this new world, memorized nursery rhymes in their new language like a native, obediently

sang the national anthem with their classmates at every assembly, helped their

mothers with the names of vegetables and meat cuts at the neighborhood grocer’s. Lispector would grow to master the most

beautiful, intricate literary language of her adopted country. Berriault was credited, among other things,

for her mastering the language of an amazingly wide range of characters, be

they male or female, and from all social, ethnic, and economic backgrounds. Despite this apparently thorough adjustment, both

wrote as if they viewed the world as a refugee camp.

Even well after notoriety

came, the lips that refused to smile, in the photos of both women, exercised

the same magnetism as the tenor of discomfort in their prose. The strength – and vulnerability – of their

characters sprang from the awareness of how little it might take for anybody to

slip into insanity. In Lispector’s Viagem

a Petrópolis, Mocinha, the protagonist, seems undisturbed by her

isolation, yet her “teary eyes, permanent smile” indicate unspoken sadness and

the will to be noticed. To the other

characters in that story it seems that she is unaware of her strangeness, but

she gives plenty signals of her unfathomable solitude. The same sense of aloneness even among

comrades is frequently the essence of Berriault’s main characters. In “The Diary of K.W.,” a sixty-three-year-old

woman who has no friends or relatives, and is unable to keep a job, is dying of

starvation. In her diary entries she

gradually reveals that she was once married and successful, but is now so

immobilized by fear, loneliness, and poverty that she is unable to ask for help. She addresses her neighbor, a young man whom

she has never really met, in a monologue that suggests dementia, yet she makes

perfect sense.

In an ending to a

short story emblematic of Berriault’s work, a woman lies in bed of a stranger,

fully clothed beneath the covers and still wearing her dark, style-less

coat. Or in another, a twelve-year old

boy cannot bring himself to talk about his older brother’s death, accidentally

caused by the younger boy’s gun. He is

isolated among his family in what is likely his, or anybody’s, darkest

hour. The woman’s coat, a not-so-distant

call from Samsa’s insect carapace and from Gogol’s Overcoat, and the boy’s

incommunicability with his family, map out some of the kafkaesque heritage on

her work. Critics of Lispector’s work have

also frequently named Kafka, as well as Gogol, as a source of nourishment: in the penchant for surrealism and the

grotesque, an affinity for realistic detail, and the ability to satirize the

absurdity of modern society.

By far one of the

most elemental influences on any author’s work stem from their relationship

with their parents, and here, too, these two women share a tragic bond. Lispector’s mother died when she was nine

years old, which soon caused her to seek work as an adult responsibility. Similarly, Berriault’s mother went blind when

she was a teenager, which, similarly,

resulted in her having to take up a job and help support the family. Both writers refer to this loss not in notes

of self-compassion, but as a path to creating characters out of darkness, which likely haunted both teenagers

in the attempts to come to grips with their fractured happiness Many of their characters are always on the

move, albeit often en route to nowhere in particular. Their discomfort, amply shared with the

reader, is physical, often caused by travel or dislocation. Either of these authors, for instance, could

just as easily have used the earthquake image for the appearance of a mental

hospital each morning, where characters, upon waking, ask themselves, what has happened

here? In Rafael Puertas de Miranda’s

words, they wrote as if their narrative was gagged beforehand, circumscribed to

small space on paper. Their impact came

from sharp, pointed text that did not digress. The reader was continuously assaulted by their

trigger-happy pen.

Berriault has been

said to join the circle of writers which includes Dostoyevski, who, in probing

the human psyche, find, as she says in The Lights of Earth a need to “dispel

a little of the vast abandonment the world casts on everyone’s face.” In Lispector’s Viagem a Petrópolis,

Mocinha’s wonderings in the streets of Rio de Janeiro or sitting on a park

bench, would be her personal escape route from the sense of abandonment to find

the landscape of the homeless. Silent

monologues, or sometimes not so silent, lead to epiphany and raw

self-knowledge.

In both women’s restless

prose, rich with poetic imagery, it is clear that obscurity isn’t so dreadful

after all, one is as unknowable to the world as the world is unknowable to her. Although both reached literary recognition

early on in their careers, they were willing to pay a hefty price in fame in

the name of their true voice. Their purpose,

as authors, was not to reach the end of the story, it was rather to know pain,

to understand the suffering of others, even at the cost of feeling it himself. Their refusal to smile at the camera is a

reminder that there is a fine line between flailing and the fully lost, and the

lost do not smile. Even more poignantly,

Berriault and Lispector brought to life women who become meaningless as they

age: under their pen, an old woman could

be disregarded to the point of invisibility. These two women, separated by Geography more

than any other force, knew that solitude follows you wherever you go. The meaning of their work does not wean as it

ages. It is silent yet undeniable

testimony, of struggles past. “The silence [in the room] was like an

invasion, a possession by the great silent mountains.” (GB)

-x-x-x-

Poeta falando (bem) de poeta: Cyro de Mattos teve a generosidade de me permmitir publicar sua crítica sobre

MEMORIAL DA CASA DA TORRE

Stella Leonardos

LEIA E DESCUBRA QUEM É STELLA LEONARDOS

E O QUE É A CASA DA TORRE

texto abaixo enviado por Cyro de Mattos*

-x-x-x-

Autora muito premiada, com

destaque para nove láureas concedidas pela Academia Brasileira de Letras,

Stella Leonardos publicou mais de duzentos livros, entre volumes de romances,

poemas, literatura infantil e

dramaturgia. Formada em Letras Neolatinas, tradutora do inglês, francês,

italiano, espanhol, catalão e provençal, sua estréia aconteceu com Passos na areia , em 1941. Os críticos costumam situar a vasta

obra poética de Stella Leonardos na terceira geração do Modernismo,

relacionando, nessa condição, os livros Geolírica

(1966), Cantabile (1967), Amanhecência (1974) e Romanceiro da Abolição (1986).

Nome dos mais festejados pela crítica,

Stella Leonardos vem entregando há muito tempo

sua vocação poética ao projeto de recriação de um Brasil bem brasileiro. Da sua alma

cancioneira e romanceira salta um Brasil de sentimentos românticos,

epicidades, ideais, relatos e saberes

populares. Brasil iluminado de estados líricos, formado por elementos míticos,

que irrompe do lugar onde nasce a

história feita de passagens marcantes, ações, tantas razões e casos.

O épico apresenta, o lírico lembra, o

dramático articula mundos interiores no eixo do ser-estar, movido pelos

instantes dos seres humanos e criação da

vida. No palco da duração crítica e contínua dos acontecimentos expande-se a poesia de Stella Leonardos. Conota essa

maneira íntima do lírico, calcada em permanente mergulho na memória, feita de

emotividade, cena histórica e pesquisa. Gentis seus versos, em Memorial da Casa da Torre recordam

vivências nas arcadas, aludem a finíssimos lavores nos salões e aposentos.

Abrem-se nos portões com senhores de terras na conquista. Tocam no

berço territorial de nossa Pátria, no músculo dos negros, no fôlego dos índios.

Restauram o homem através de intenções, ímpetos, sonhos e idealismo. Passado,

nessa poesia reveladora de um racontar acurado, é escutado no desassombro de nossas gentes, vencedoras de sertões na

música rústica das boiadas.

Poesia é emoção condensada em

linguagem, rica, tensa e ambígua. Reflexão em suas formas geométricas calcadas na

imagem, sob o pretexto da escrita para

revelar uma idéia. Em Stella Leonardos mostra um discurso significante pontuado pelo som, no ritmo que ela imprime

em sua maneira particular de sustentar a ideologia. Sua palavra cantante

escorre musicalmente com interferência de vozes, tornadas dinâmicas,

apropriadas, nas lembranças e cenas descritas.

O registro que é feito do fato bom ou

triste é mais endereçado aos ouvidos do

que aos olhos. Sua dicção musical enceta versos que dialogam com a história,

ecoam no que repercutiu procedente de alguém que permaneceu no tempo. Em seus cancioneiros e romanceiros tão

brasileiros, Stella Leonardos canta e conta. Revive o Brasil com maestria de

poeta que encanta, consciente de que no

rememorar tudo é ilusão, sonhar é sabê-lo, como falou Fernando Pessoa..

Assinalada a terra por armas e brasões

de uma gente remota, que aqui chegou por mares nunca dantes navegados, o

governo português teve que enfrentar situações desfavoráveis para fazer a colonização. Um desses

obstáculos consistia na imensidão da terra descoberta, com a sua mata de sono

milenar, jamais incomodada. Foi necessário dividir a terra rica em capitanias,

glebas de muitas léguas, e doá-las àqueles que tivessem condições de fixar o

homem no solo.

Por quase três séculos, a Casa da Torre

distendeu suas cordas e acordes de inúmeros serviços prestados ao Brasil,

começando pelas guerras aos piratas, aos holandeses e da Independência. Dali

partiram os primeiros desbravadores do

Norte brasiliense, as intrépidas bandeiras, as principais entradas dos sertanistas

do Nordeste.

Em Memorial

da Casa da Torre, um dos episódios mais significativos da história do

Brasil Colônia, oriundo da influência da prole mameluca de Garcia D’Ávila, que

levou domínio e ambição às regiões desconhecidas, Stella Leonardos, hoje com

idade avançada, demonstra que ainda domina bem o verso e faz uma poesia

cativante, bebendo na tradição da poesia de todos os tempos. Usa

o arcaísmo e o neologismo para narrar os acontecimentos da Pátria nascendo a

passo de marcha. Na decorrência de versos que se alteiam com vozes em coro, de

viva gesta, acende sinais luminosos da

labareda que haveria de contribuir como ideal de heroísmo, cultura e

civilização.

É da tradição da poesia ibérica vazar o

amor e a saudade como figurantes que convergem para o lirismo e o épico. O

registro de vultos e fatos heróicos são recorrências manejadas por rapsodos

com inspiração no populário e saberes

anônimos. No caso de Stella Leonardos, o relato

poético se municia de pesquisa e de saberes locais do populário. Atenta, a poeta não se descuida de

rimar memória e fatos que melhor

repercutam ao fazer modelar do nosso

cancioneiro e romanceiro. Seus

livros aí estão espalhados para que sejam lidos como resultado da aproximação

mágica de uma alma sensitiva à nossa memória, arrebatada de sentimentos

românticos, valendo-se do histórico por quem ama a beleza e o valor

exercido pela estima da Pátria.

No poema “ In Memoriam”, introdutório

ao assunto deste Memorial da Casa da Torre, Stella Leonardos abre seu verso terno

para o que vai contar e cantar, com leveza deixa ser conduzida pela

inspiração que lhe é particular:

No barro desses tijolos

Por mãos

índias acalcado

Quanta voz índia

não dorme?

Na

alvenaria da pedra

Por mãos afras

carregada

Quanta voz

negra não pesa?

Na torre desse

Castelo

Por brancos

rostos vigiada

Quanta saudade

não se ergue?

A autora desses versos torna

suficiente a imagem que interpela e, ao mesmo tempo, contempla a passagem do

tempo guardada na memória. Apoiada na

sensação do que se refaz triste, sob um

ritmo que atrai, nos embala e envolve até o final da cantiga.

Como estratégia usual de seus cancioneiros e romances, ela sabe tirar efeito na

linguagem quando emprega o neologismo através dos vocábulos que inventa: saudadeado, largoandante, longivozes,

multivária, plurilínguas, existenciar, surpresada, passilargo, fugileve,

impulsada, noviterra, ensonho, sonoite, novihorizontes, azulando.

A Casa da Torre é a primeira grande

fortificação portuguesa do Brasil. As pegadas dos valentes que a povoaram com

desassombro inigualável dos tempos de Garcia Dávila renascem neste memorial poético de Stella Leonardos. Da

cidadela em ruína, muralhas cobertas de

musgo, gestos que resvalam por entre sombras, das fendas e rastros do poder extinto, reencontramo-nos na

poesia de versos generosos. Das

paisagens com passagens cheias de histórias marchamos, somos levados com

o mesmo brilho das gerações que fundaram nossa nacionalidade

Referência Bibliográfica

LEONARDOS,

Stella. Memorial da Casa da Torre,

Gráfica Santa Marta, João Pessoa, Paraíba, 2010.

·

Cyro de Mattos é escritor e

poeta. Premiado no Brasil e estrangeiro.

HOMEM EM QUEDA: Book Club da Hebraica

-x-x-x-

FALLING MAN

Don DeLillo

Homem em Queda

"Homem em queda surge como a única obra verdadeiramente artística a lidar com os terríveis eventos de 11 de setembro de 2001, em Nova York. A leitura deste novo e surpreendente romance de Don DeLillo equivale a olhar-se em um espelho e contemplar uma cara familiar como se fosse pela primeira vez." - Newsweek

"O livro é angustiante, os fatos não seguem uma sequência aparente, os personagens são deprimidos e inseguros". Então pra quê ler o livro?

| "Falling Man" (Richard Drew) |

Ah, aí é que está: como ficou claro no Clube de Leitura, o autor cria este ambiente cinza, pessoas cinza, vidas cinza, e você se vê nele. Você vira as páginas, esperando que algum dos personagens saia deste torpor, retome as rédeas de sua vida... mas não acontece. Don DeLillo foi cirúrgico na precisão, atingiu exatamente as terminações nervosas do otimista, do equilibrado. O leitor "sai" da última página com a sensação que acaba de acordar de um pesadelo: o 11 de setembro.

Discutiu-se todas as camadas do livro: a política, a comunitária (de New York, mas São Paulo também), dos indivíduos. Alguns viram na descrição do terrorista nada mais do que a realidade, outros viram uma tentativa de humanizá-lo. Tratamos da importância dada à memória e sua perda, nos personagens com Alzheimer's, da futilidade em fugir do destino.

Falamos sobre o filho, Justin: ele é um adolescente revoltado normal, ou demonstra distanciamento patológico? E a pergunta óbvia: qual é a parcela de culpa dos pais nesta relação fraturada?

O mais importante: quem é o homem em queda? Quem está caindo? Muitas respostas, ressoando com as da crítica especializada: o homem em geral; a nossa civilização; nossas vidas particulares.

Não é um livro fácil de se ler. Mas a conclusão foi que vale a pena. Próximo livro: Nêmesis, de Philip Roth.

-x-x-x-

FALLING MAN

Don DeLillo

Homem em Queda

ANO: 2007 (publicação original em iglês)

EDITORA: Cia das Letras

264 páginas

Keith consegue sair com vida de uma das torres gêmeas

atingidas pelos aviões pilotados por terroristas, no fatídico 11 de setembro de

2001. Em vez de voltar para o seu apartamento, o atordoado Keith, coberto de

poeira e sangue, e carregando uma pasta que não lhe pertence, bate à porta de

sua ex-mulher, Lianne, com quem tem um filho pequeno.

Keith tenta reconstruir sua vida, ao mesmo tempo que sai em

busca do dono da misteriosa pasta. Lianne, por sua vez, trabalha como

voluntária junto a pacientes com Alzheimer e cuida também de sua mãe, Nina, uma

historiadora da arte aposentada.

Esse punhado de personagens evolui num mundo onde não há mais

o antes, e o depois

é todo feito de incertezas e angústias com pouca chance de resolução. Da fatura

dos diálogos, restritos à essência mesma do coloquial, à busca de afinidades

entre os dramas pessoais dos personagens e os acontecimentos históricos, Homem em queda nos mostra o

ataque fundamentalista a Nova York como uma monstruosa metáfora da nossa

civilização.

"Homem em queda surge como a única obra verdadeiramente artística a lidar com os terríveis eventos de 11 de setembro de 2001, em Nova York. A leitura deste novo e surpreendente romance de Don DeLillo equivale a olhar-se em um espelho e contemplar uma cara familiar como se fosse pela primeira vez." - Newsweek

Watch the video on 9/11, and think about how your life was affected by the attack. (Assista o vídeo sobre o 9/11, e reflita sobre a maneira em que sua vida foi afetada pelo ataque.)

Think about the photograph that originated the title of the book:

(Pense na foto que deu origem ao título do livro:)

If you haven't read the book yet, don't wait any longer. If you did, and want more, read:

(Se você ainda não leu o livro, não espere mais. Se leu e quer mais, leia:)

- Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close (Jonathan S. Foer)

- Saturday (Ian McEwan)

- The Emperor's Children (Claire Messud)

- Windows on the World (Frederic Beigbeder)

-x-x-x-

COLTRANE BALLADS

(Carlos Felipe Moisés, Noite

Nula, Nankin, 2008)

Esse é um poema que me emociona a cada vez que o leio, por isso me senti desafiada a descobrir os ingredientes mágicos. A crítica Andréa Catrópa teve a generosidade de publicar minha crítica em seu blog criticadiversa.blogspot.com.br

De pai para filho, de alegria e desespero:

“Coltrane Ballads” é um poema

que usa a linguagem musical para demonstrar o vínculo entre pai e filho, a

tentativa “de criar um pendant verbal... lidando com as palavras como massas

sonoras, não só como conteúdos,” segundo o próprio autor, em entrevista a

Ricardo Silvestrin. É através da relação

do sujeito poético com a música de John Coltrane que o leitor descobre a perda

do filho, a dor insuportável que isso causa ao pai, e a remota esperança do

reencontro. Dividido em quatro partes

desiguais, numeradas, o poema começa, no primeiro segmento, com o registro dos

tons e instrumentos ao fundo (“sax tenor... agudos/ suaves..). Em tom intimista, entra a voz poética em

primeira pessoa, a revelar que essa música ficou no passado, na memória, “Desde

então sei/ de cor. Nunca mais ouvi mas/

sou capaz de cantarolar nota/ por nota...”

A tristeza contida prenuncia-se mediante esse “então.”

O segundo segmento tem um tom

mais prosaico. É um diálogo entre pai e

filho (“Emprestou né pai?”), sobre uma conversa do filho com um amigo. Ao dar voz ao pai e ao filho, o poeta dá

concretude ao sujeito do poema e a seu interlocutor, e os aproxima do

leitor. A música de Coltrane os une: o pai dá ao filho o CD (ou vinil?), “Pode

ficar : é seu./ Você/ ouve melhor do que eu”./

Tem-se a sensação de intimidade partilhada com o leitor. A angústia, vagamente sugerida no segmento

anterior, intensifica-se e começa a tomar forma. Apesar da emoção contida, as quebras nos

versos, e o deslocamento lateral da palavra “Você” referindo-se ao filho, lembram

uma pausa por embargo na voz poética, um nó na garganta. O segmento, que começa distante, no tempo

passado (“Um dia ele ouviu...”) termina no presente (“Pode ficar: é seu./ Você/

ouve melhor do que eu”). O leitor sabe

que está diante de algo muito grande, maior do que o sujeito do poema, mas

ainda não é possível definir-se a origem dessa angústia. As rimas, raras, dão leveza aos versos (me

viu, sorriu; me deu, é seu, que eu).

Nada prepara o leitor para o que vem a seguir.

É avassalador: “a casa toda desmorona,/”. No terceiro segmento a voz poética se

descontrola. Surge uma torrente de metáforas

contundentes em numerosos versos que se deslocam no papel, ora para a direita,

ora para a esquerda, tal qual águas que se extravasam repentinamente de uma

represa. É o desespero em palavras. Em contraste com o segmento anterior, nada há

de prosaico aqui. A referência ao nome

de duas faixas do Ballads, “Say it, Over and over again,” e “You don’t know

what love is,” também são pistas do que o sujeito poético ouve: repita outra e outra vez, tente, tente, e a

voz na noite nula que diz, quase em tom acusatório, você não sabe o que é o

amor.

Nesse segmento estabelece-se a

filiação do poema ao livro, Noite Nula,

no verso “...no meio da noite/ nula uma voz reboa...”. É no desespero, na inutilidade de lutar

contra o esmagamento, “Tentei, tentei, continuo a tentar...” que esta voz se rende, “...não ouço/ mais

nada.” Todos os poemas do livro, afinal,

dão vida a pessoas mortas, uns com mais, outros com menos carga emocional, mas

todos com a marca da memória, de impedir que sejam engolidos pela noite nula. Noite nula é noite de perda: na noite nula,

algo se desintegra. Carlos Felipe

Moisés não poupa o leitor, explora todas as possibilidades, por crer que nenhum

fato seja indizível.

No último segmento há a volta à

contenção através da disciplina da música e da economia de versos. Nada resta se não sonhar com o reencontro:

“...um dia/ vamos ouvir tudo de novo/ lado a lado”. A repetição dos dois agudos, suaves

sequências, “ouvidos” no começo, fazem o papel que fariam no jazz, de retomar

alguns acordes, mas não fazer tudo igual, criando um novo nuance com os mesmos

elementos. Dá à perda uma nova dimensão,

a da eternidade que separa este pai de seu filho. É justamente ao sonhar com o dia do

reencontro que o sujeito do poema faz lembrar que esse dia não chegará enquanto

ele viver. O leitor sente a dor deste

pai. Na melhor tradição pessoana, Carlos

Felipe Moisés finge:

O poeta é um fingidor.

Finge tão completamente

Que chega a fingir que é dor

A dor que deveras sente.

E os que lêem o que escreve,

Na dor lida sentem bem,

Não as duas que ele teve

Mas só a que eles não têm.

(Fernando Pessoa, Autopsicografia)

WHERE IS LATIN AMERICAN LITERATURE

GOING?

| Carlos Fuentes |

With Carlos Fuentes recently deceased, Garcia Marquez' health failing, the Boom Generation is disappearing. Here is an update on names to follow - and to read - that are recreating the momentum, but on different premises. It's 40 minutes long, but well worth it. From minute-15 on, my ex-student, (now Dr.) Ingrid Bejerman is interviewed. Got pencil and paper? Go!

http://www.guardian.

| Julio Cortázar |

-x-x-x-

HIATO ENTRE AMOR E MORTE

minhas impressões sobre o poema Hiato, de Armando Freitas Filho

HIATO

Amor de mãe, amor de hérnia

que mesmo distante, mesmo morto

é herança que atravessa o intervalo

com seus tentáculos e tentativas

de aranha, tantalizante, e agarra, prende

por dentro: morrerá comigo, furioso.

Fiel tatuagem imune ao tempo de origem.

(LAR, , Cia das Letras, 2009)

“Hiato” é um dos poemas da coletânea de 2009, publicado,

portanto, por Armando Freitas Filho (AFF) já com mais de sessenta anos. Talvez por isso, já de início, aproxima dois

fonemas opostos, extremos, da vida: amor

e morte. É um poema em 7 versos, que

contem 2 sentenças sintaticamente completas, pontuadas, a primeira com 6

versos, e a outra com o último. Com

riqueza de recursos de linguagem, tais como o paradoxo e repetição, o poema

hora estrangula, hora tantaliza, mas não solta o leitor nem por um segundo para

recuperar seu fôlego, do primeiro ao último verso. Abre com paradoxo, “Amor de mãe,

amor de hérnia/”, golpe que baixa a guarda do leitor, para em

seguida garroteá-lo, com metáforas de predadores

peçonhentos, “tentáculos” (de polvo? de anêmona?), “de aranha...”, que agarram,

prendem, paralisam “...por dentro.” Na voz do poema, é o

amor de mãe que mata.

AFF utiliza-se de recursos sonoros elementares para construir uma estrutura concisa, mineralizada.

Há o poderoso eco de morte em

amor (“Amor de mãe.../...mesmo

morto/”), aliterações “quentes,” com “m”

(amor, mesmo, morto, morrerá, comigo, imune, tempo) e “frias,” com “t” (morto, atravessa, intervalo,

tentáculos, tentativas, tantalizante, dentro, tatuagem, tempo), duplo sentido

(“...agarra, prende/”, ou: a garra prende/).

Com esses recursos, além da ocupação no papel, centralizada, e do

conteúdo, memorialístico e ao mesmo tempo muito próximo à pele (“Fiel tatuagem...”),

resulta um poema de profunda elaboração psicológica. É quase um epitáfio.

A voz do poema, em ritmo orgânico, pontuado, é a de uma

luta: começa por raiva (versos 1 ao 5), em seguida vem a vingança ou vitória (verso 6), e termina no conformismo

(verso 7). O próprio número de versos

dedicado a cada fase desse embate indica o grau de dificuldade dessa

elaboração: há muita raiva a ser

dominada, e isso acontecerá na morte, quando essa voz poética irá aprisionar seu algoz (“morrerá comigo, furioso./”) .

Nesse verso há a aceitação da inevitabilidade, da permanência desse

amor. Da criatura “amor de mãe” que

surge no primeiro verso, sobram dois mortos, filho e mãe e a “fiel tatuagem imune

ao tempo de origem.”

AFF refere importante influência de Carlos Drummond de

Andrade, particularmente de seus poemas memorialistas, porém nesse poema não há

distanciamento, não há uma gota de

humor, há sim a auto-vivissecção sem auto-piedade, a investigação, parcialmente

respondida, sobre amor e morte. Ao

final, o hiato, o brilhante retorno “...ao tempo de origem.”

----x----

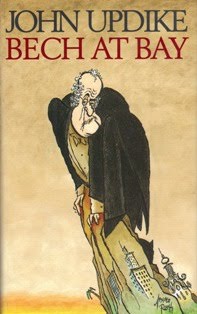

John Updike and Philip Roth:

intimate confessions of a universal nature

Two Jewish writers, protagonists, trilogies. Caught in the drama of the

arc of creation, both dwell deeply in life’s lowest moments: envy, anger,

murderous thoughts (or action). Updike’s

Bech and Roth’s Zuckerman both mold their not-so-mock-heroic tales from

their lecherous, self-absorbed, personalities, lost in a brave new literary

world. Both confess their sins fully, either in first person or through

the omniscient narrator. As an example, in Updike’s Bech at Bay cover,

Bech is perched, in his tuxedo, on a mountain-top, like a vulture, looking

below with suspicion and a sense of well informed skepticism: the elements of

paranoia? If so, and even if not, the same traits are in Nathan

Zuckerman’s persona. But both go well beyond the easy label. In

Roth’s The Human Stain, as an example, the cover shows a black shadow

in the shape of man walks, hunch-backed, as if suspended on a gray background

that could be the sidewalk, or the city from above. Who are these

vulture-like men, what burdens their backs so?

Identity. Defining it is life’s oxygen, unattainable for the

Jewish soul, according to many. Philip Roth is Jewish and John Updike was

not, but they were American contemporaries in one of America’s own identity

crisis, the 60’s. Updike was doing well, both from the critics’ and the

readers’ point of view, but there had to be the pressure of the giant Jewish

American novelists, I. B. Singer, Malamud, et al. So Updike

confessed: Bech struggles with

the Jewish versus American identity (“can’t you be both?”), and is derided by

both Jewish and WASP critics, but wins the Nobel in Literature in the

end. His point? The prize says nothing of literature, while it

speaks volumes of man’s refusal to recognize his own pettiness.

And Roth is constantly reminding us of that.

Zuckerman is not a nice man, but a “real” one, nonetheless. Real enough to

be Roth’s spokesman (The Facts)for his intimate struggles

in marriage, his self-derision, his recognition that the best is yet to be

written. So he keeps writing. The identity problem is not resolved

by reducing his universe to Jewish families from Newark, on the contrary, each

finds in a “real” million little pieces, fragments of everything they want to

wield into one. Each character is not Roth, but rather a facet of

Roth. That is where the author begins and the characters end.

Both are universal in essence, by stabbing the illusion that one is

whole, Jewish or not. How bad are you willing to be in order to do

good? Will repentance assure immunity from such vulgarity? If you

have children, aren’t you making a statement of optimism? If you write

one more book, isn’t that bearing a child? Yet the works of both, but

Roth’s in a particularly heinous vein, have at times been objects of voyeurism

rather than of literary hunger.

There is no escape from morbid curiosity, least of all in literature,

but to bank yet a single line of these two prose masters on the easy appeal of

peeking into their innards, even if veiled by humor, is to do them an injustice

and to prove illiterate. There is as much of us in their books as there

is of them. “We all have two lives: The true, the one we dreamed of in

childhood and go on dreaming of as adults in a substratum of mist; the false,

the one we love when we live with others, the practical, the useful, the one we

end up by being put in a coffin.”

Fernando Pessoa

Fernando Pessoa

Hurried exodus from Egypt and Iran:

two girls, their fathers, their pain

Dalia Sofer and Lucette Lagnado

The

Septembers of Shiraz The Man in the

White Sharkskin Suit

Dalia Sofer* Lucette Lagnado**

**2008

recipient of the $100,000 Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature

Two households, both alike in dignity. Two families whose tragic fall is

precipitated not by their own flaws, but by changes in the political environment. In both cases, the story is told by a

daughter who lived through it all while clinging to the image of a loving,

powerful father.

Is it a coincidence that the cover of both books is so similar? Now look closely at the pictures of each author: the long, dark hair and the direct gaze are also very similar. Both paint a picture of loss, of lands far away, a story to tell.

Is it a coincidence that the cover of both books is so similar? Now look closely at the pictures of each author: the long, dark hair and the direct gaze are also very similar. Both paint a picture of loss, of lands far away, a story to tell.

“The Septembers of Shiraz” is a powerfully affecting

depiction of a prosperous Jewish family in Tehran two years after the 1979 revolution,

where millions of ignorant, poverty-stricken people were falsely promised

equality and prosperity at the cost of turning in fellow citizens for suspected

or alleged “sins” against the new order. On September 1981 Isaac Amin, a

self-made, successful Jewish gem merchant approaching 60 is arrested by two

armed Revolutionary Guards, kept in prison and tortured for a year. His crime: he has, to his grave danger, been

patronized by many in the aristocracy, including the wife of the shah.

Told in the third person, largely in the present tense, the intersecting

narratives follow each member of the Amin family over the course of their most

difficult year. Each has their own

demons to deal with: the sense of guilt

and betrayal, the yearning sense that one did not do enough to give comfort,

and the inevitability of loss, all the while knowing

that nothing compares to what Isaac is going through. Although they are never allowed any news much

less any visits, they know about the torture that routinely occurs in

Revolutionary prisons. When he is

finally released, they have to adjust to this stranger who comes home, but the

family ties truly surface in face of danger and the urgent need to escape Iran.

“The Man in the Sharkskin Suit” is also about a Jewish family fleeing Egypt

in 1963, a hitherto friendly environment, where Jews had been living for

centuries completely at home. At the

center, there is also a self-made man who came from a very primitive family

(his mother could barely read), a man who mastered 7 languages, well liked by

members of every sector of Egyptian society, from fishermen to the king. Differently than European Jews, Sephardic Jews

were not affected by the

Enlightenment until the 20th century, and

dressed, ate, spoke, in a manner almost indistinguishable from their Arab and

Persian compatriots. The Jewish value on

education, reading, writing, mathematics, science, astronomy, learning foreign

languages, reinforced by historical limitations on land owning and rural

activity, were some of the channels that enabled Jews to attain prosperity in

each of these countries and eventually contributed to their elevation in social

and economic status.

Thus it was that in Lagnado’s book, the account of her family’s fall

from privileged circles in sophisticated Cairo to refugee status in Paris and

Brooklyn, is parallel to Sofer’s, from Tehran to the U.S. In Egypt the political change that resulted

in prosecution of Jews started in 1952, but the family did not escape until

1963. A recurring question comes

up: why did they wait so long? And why did the Amin’s wait for two years,

when they could have left earlier in better conditions?

The answer is also a recurring one in Jewish History: they could not believe things could get so

bad in a country they had considered home for centuries, where they had been

allowed to reach the highest echelons of society. It happened in Germany, it is happening in

France and in Venezuela, and still they won’t leave until it is almost too

late, in fact too late already, for some. As in the words of Isaac Amin’s

sister, their reasons for staying, at the time of the revolution were not so

far from those given by any Jew, any time: “If we leave this country without

taking care of our belongings, who in Geneva or Paris or Timbuktu will

understand who we once were?”

The daughter in each novel clings to a symbol of times

past: in Lagnado’s account, it is the

wedding picture of her parents, which, she knows is somewhat staged, yet it is

a symbol of the father’s loyalty to the family:

the thought of leaving without them, of saving himself before others,

never occurs to him. In Sofer’s book

there is a sapphire ring which was given by Isaac to his wife, that goes missing

when he disappears, but the ring turns up eventually, and you begin to suspect

that Isaac will come home, too. The

power of such objects goes well beyond literature. Whether these two symbols existed and had

this role in real life, or not, both authors use the concept in a candid, disarming,

young girl way.

The subversion of

the Exodus is of a piece with the subversion of identity which Lagnado

painstakingly anatomises. Sofer uses a more complex route to dissect this

monster: Amin’s son, who is in college

in the United States, struggles with identity in terms of piousness,

nationality, family ties. He is at once attracted to ways quite different than

those of his origins, and inseparable from his family, home, even the servant.

These paradoxes of

exile are as fundamental to Jewish experience as they are to the nature of

Jewish identity. Leon, in Brooklyn, longs

to return to Cairo, Isaac to Shiraz, not the geographical locations but rather

the continent of memories. Both novels repeatedly suggest that life’s significance derives less

from ideas than from the most basic, the most concrete shards of memory.

As a writer, molecules of

memory is what I breathe. I, too, have

scars in my hands, from hurrying through Jewish ghettos over the

centuries, half-carrying, half-dragging heavy leather trunks, filled

with wrinkled images

and children’s voices singing in ladino, Yiddish, Old English.

Michel Laub**

Grandfather, father,

son.

In tinkers, an old man lies dying.

Confined to bed in his living room, he is hallucinating, in death throes from

cancer and kidney failure. A

methodical repairer of clocks, he is now finally released from the usual

constraints of time and memory to rejoin his father, an epileptic, itinerant

peddler, whom he had lost 7 decades before. In order to tell his father’s story, the dying

man tells his grandfather’s story, as well, but through his father’s eyes. This alone would have made Harding’s work

unforgettable, daienu, but there is

more, much more.

Laub’s diário da queda begins with

the story of a thirteen-year old boy who has an ugly fall during his birthday

party. The narrator is an adult who was one

of his classmates, and who at the outset lets you know the fall was no

accident. The story unfolds as the

consequences of that event to his life, but in order to understand them, he

tries to understand his father, and realizes that his father can only be

understood in light of his grandfather’s story, which begins with his survival from

Auschwitz. Thus the parallel in

theme: father-son relationships, and how

events in one’s life can define one’s children and grandchildren.

Neither

book has a plot in the traditional sense. Instead, in both, the story comes in

layers and images: in tinkers, as the

recollections of a dying man, and in diário

da queda, as the assembling of memories of a grown man trying to be a

better person. Again, a relevant

similarity: memory is the edge of a new beginning.

Both

Harding and Laub made me think, in a very personal way, about the way families

lay down unimpeachable tracks on future generations. Neither complacent nor

indulgent, both books speak of guilt and pity, of cruelty by silence between

spouses, or between father and son, of abandonment of a child or of a gravely

ill spouse or parent. Laub, on pity, goes

beyond, by having the courage to tackle a monumental topic, the Holocaust, yet in

a new perspective: survival is not enough, one must indeed start over.

In

several interviews, both authors denied that their book was autobiographical,

but both agreed that they had autobiographical elements, Laub in reference to

the significance of the Holocaust, and Harding, the impact of epilepsy on his

grandfather’s family. Regardless of the motivation,

one is imperceptibly immersed in each layer of the story. In tinkers,

at one point you want to abandon the omniscient narrator just so you can listen

to George a bit longer, and in diário da

queda you are similarly content to sit in the narrator’s study, listening

to him and perusing, at his suggestion, his grandfather’s diaries on his desk.

“Harding

takes the back off to show you the miraculous ticking of the natural world, the

world of clocks, generations of family, an epileptic brain, the human soul.”(Elizabeth

McCracken, author of Niagara

Falls All Over Again). Laub, in turn, in a very Jewish

way of studying the world, reads to you the written - and unwritten - memories

of three generations. Jewish-biologist-cum-writer that I am,

I have a long list of questions for Harding and Laub in a joint interview I dreamed

up. Care to join? Send me your impressions.

*

Winner of the 2010 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction

**Winner of the 2012 Prêmio Brasília de

Literatura for Fiction

Vivian,

ReplyDeleteAchei muito interessante e bacana. Parabéns.

Um beijão

Margrit Herzberg

Hi Vivian,

ReplyDeleteI really like the idea of pairing up the books!

All the best,

Douglas Takeuti

Thanks, Douglas, and how about sending me suggestions of good books, whether in pairs or not? It can be books on anything you like, including children's books - you may want to consult with Julia on these!

Deletebeijo

Hi Vivian,

ReplyDeleteI really enjoyed your poems and literary criticisms. Have you read Sarah's Key yet? That might be a good one to compare to other similar books. On a whole other topic, I recently read the South African book, The Native Comissioner, and wholly recommend it. It deals in guilt, opression, morality, vanity and their interface with sanity/insanity while telling the story of South Africa from before the aparthaid.

Hi, Vanessa, I have been meaning to get to Sarah's Key, now I will! I have not read The Native Commissioner, but will get to it as well. Thank you for the recommendations, I am starting a Reading Club at Hebraica very soon, and people there read a lot, so I need to come up with good books that are not yet so well known. Thanks, beijo.

DeleteI think you'll enjoy it and I can lend it to you if you want! Beijos , Vanessa

ReplyDelete